Art records what people feel, how they live and who they say they are. In India, artists who began to work after independence took those records in new directions. Jogen Chowdhury belongs to that group. He draws curved, unbroken lines with ink or pastel – the lines outline men and women who slump, stare or touch one another. The same lines recall Kalighat pats besides Bengal scrolls, yet the cramped rooms, empty cupboards plus bare bulbs in the pictures belong to the present. The bodies look thin and tired, but their straight backs and locked ankles show they still hold themselves up.

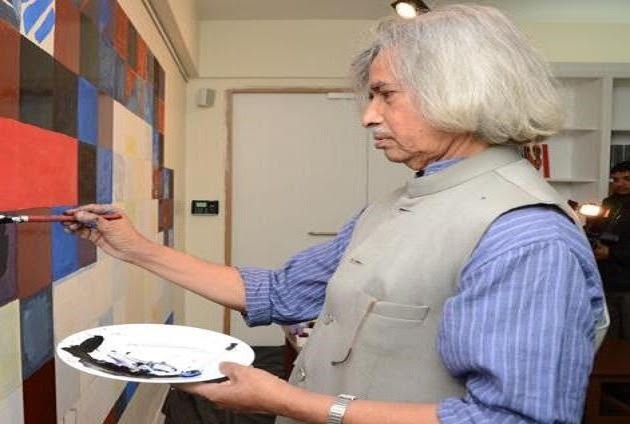

The Artistic Journey of Jogen Chowdhury

Jogen Chowdhury was born in 1939 in Faridpur, now part of Bangladesh. He spent his childhood amid political unrest and the violence of Partition – these years fixed his attention on the daily hardship of ordinary men and women plus that concern later filled his paintings – he first trained at the Government College of Art besides Craft in Kolkata – moved to Paris to study at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Contact with European modernism widened his visual vocabulary, yet he kept close to Indian stories and methods. He set foreign devices beside local themes and the mixture gave his work a distinct place between the regional but also the wider world.

His first pictures tested many shapes, but a clear manner soon appeared – it rested on long, pliant lines. The lines did not simply mark edges – they acted like separate organs that carried feeling, pressure and motion into every figure.

The Power of Lines in His Work

Jogen Chowdhury’s pictures stand out because he controls every line. The line is not an edge – it pushes, pulls and breathes. His drawings plus paintings show bodies whose arms, legs or torsos stretch or shrink, yet the viewer feels addressed in private. The bodies lack correct measure, but they broadcast plain feeling – isolation, want, fight and expectation.

Chowdhury does not chase camera like accuracy – he bends shape to tell what is real. A hip arcs too far, an arm grows two extra joints but also skin carries cross hatched scars – those shifts report unrest inside and pressure outside. Sex as well as the ease with which flesh bruises recur in the pictures. He picks clerks, wives and street sellers, records their stance besides returns them to the day with weight and worth restored.

Human Emotions and Social Commentary

Jogen Chowdhury records complicated human feelings with little outward drama. The men and women in his pictures lack heroic stature – they sit, stand or lean while restlessness or private thought holds them. Their poses expose the low level fears of middle class life, the clash between what people want plus what they accept and the steady push of social rules.

The same canvases but also drawings hide a dry satire. Chowdhury lengthens an arm, swells a belly or twists a torso – sets the figure in an impossible stance – the distortion points at political abuse and social habit. He speaks plainly about the damage wrought by Partition, by famine as well as by widening economic gaps. Each picture reflects the community he has watched, yet the reflection stays free of lecture because the colour and line keep the tone calm besides quiet.

Influences and Inspirations

Chowdhury built his visual language from several sources. He studied in Paris and spent hours with canvases by Picasso besides Matisse – those painters showed him how a single curved line or flattened shape carries emotion – he also kept contact with Bengal – the quick brush stroke of Kalighat pats, the flat colours of village scrolls and the repeating motifs on cotton saris.

He lifted the feel of cloth and placed it on paper. He covered bodies with fine sets of parallel strokes that crossed at angles – skin looked like hand loomed jamdani. The mix of Parisian form or Bengali pattern gave him a space that no other Indian artist of his generation occupied.

Mediums and Techniques

Jogen Chowdhury used ink, watercolor, oil and pastel. His ink-and-pen drawings became his best known images. He controlled the pen so that each line repeated or varied in width and density – no other artist matched the result. Even when he added color, the line still ruled the surface.

He set a thick contour next to a faint wash – the contrast pushed the figure forward plus held it there. Because the tools were few, every mark carried the full weight of the emotion he wanted to show.

Recognition and Contribution

Over the decades, Jogen Chowdhury gained national and international recognition. Museums plus galleries around the world hold his paintings and institutions in India gave him multiple awards for his work.

He worked as a curator at Rashtrapati Bhavan, the President’s House in New Delhi but also later taught at Kala Bhavana, Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan. In both posts he guided younger artists and linked Indian art traditions to present day practice.

Jogen Chowdhury and the Viewer’s Experience

The viewer never stands still in front of a Jogen Chowdhury painting. The bodies swell or shrink past normal size and the eyes lock on to the onlooker. The stare disturbs, yet it recalls people once met – it pushes the watcher back into the self and demands an admission of fear, want and contradiction. The mind stays engaged – for that reason, the pictures still speak to new audiences.

The canvases refuse to serve as simple decoration – they stage meetings charged with feeling. Once the twist of a limb or the tilt of a head settles in, the odd shape turns into a mirror. The shared fact of being human replaces the first jolt and the work states that a picture does not have to please – it has to tell the truth.

The Legacy of a Master

Jogen Chowdhury holds a central place in Indian modern and contemporary art. He draws lines as his main tool plus shows emotion directly on canvas and paper. His pictures avoid large spectacle – they tell quiet stories that speak to ordinary feeling. Critics but also viewers still praise his achievement. ArtAliveGallery and similar platforms exhibit his pieces, place them online as well as send the artist’s work past national borders.

Conclusion

Jogen Chowdhury is one of India’s most recognizable living artists. He left Faridpur during the 1947 Partition, reached Calcutta as a refugee and later showed in Paris, Tokyo besides New York. The route from displacement to international notice required persistence and a steady focus on what he saw around him – he draws with a single, unbroken contour – the line fixes a slouch, a smirk or a fold of flesh plus carries the mood of the sitter. The pictures stay in circulation because the emotions remain familiar.

Trends rotate through the market every season. Chowdhury keeps the same cheap cartridge paper, the same ball point pen and the same ochre wash. A torso bulges, an arm hangs loose, a sari slips – the marks record weight, age and fatigue without apology. Viewers still stop in front of the drawings because the bodies on the sheet match the bodies they know.